Engine Out

Visibility: Ok

Temperature: 14°C, clear

QNH: 1009hPa

Location: EDAZ (Schönhagen)

Equipment: Cessna 172 (D-EDUF)

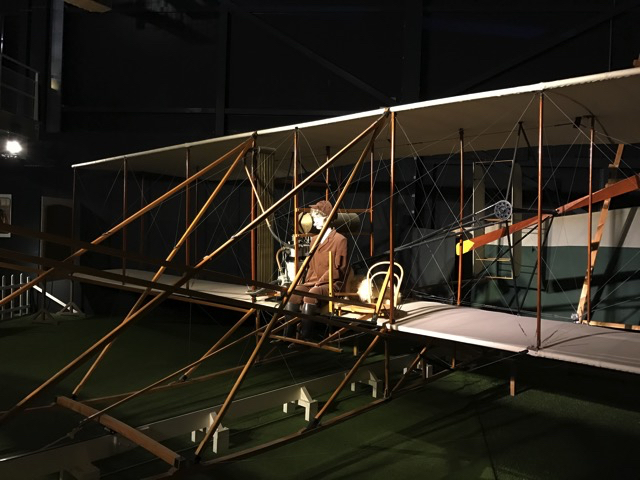

When the engine quits, the propeller does not stop turning. The airflow in flight is enough to keep it “windmilling.” Initially, the only indication of engine failure is a change in the pitch and volume of the engine noise. Then, the airspeed starts to bleed off.

Catastrophic failures with loud bangs, flying parts, smoke, and fire are rare in real life. So, the initial challenge is recognizing the engine failure and overcoming the “this can’t be real” reaction.

Once reality and perception synchronize in the pilot’s brain, a short but intense period begins. First, extend your time in the air as much as possible by adjusting to “best glide” speed. This is the speed that allows you to cover the greatest distance with the available energy (altitude). Next, choose a landing spot. Ideally, you already have one in mind, as you constantly take note of suitable landing sites while flying. Now, build a landing pattern around your selected spot. Depending on your altitude, you will fly a larger or smaller pattern and adjust your speed accordingly.

Now that you are set up for the approach, you start troubleshooting the engine. It is good practice to follow a workflow based on the layout of the specific aircraft, so procedures vary from one aircraft to another.

In this Cessna 172, I start at the top left of the panel. I check the fuel gauges (not empty), oil pressure and temperature, the primer pump (is it locked?), and the ignition (set to “both”?). Then, I pull the carburetor heat to thaw a possibly frozen carburetor, open the throttle, and push the mixture to full rich. Lastly, I check the fuel selector valve to confirm it is set to both tanks.

Nothing worked—the engine refuses to restart. If there is time, I radio in the emergency. I have done what I can. Now, landing safely is the priority, along with avoiding a post-landing fire.

This is not a pleasant topic. Chances are, I will land the airplane smoothly in the field ahead and have a great story to tell at the pub tonight. However, I am about to make contact at about 55 knots with ground of unknown condition. It might be soft. There may be irrigation ditches, badger holes, or tree trunks. I could rip off the landing gear or even flip the airplane over.

To prepare for that, I execute the second emergency workflow. Since I have given up on the engine, I kill the ignition—it could produce sparks that might ignite leaking fuel after impact. Moving along the panel to the right, I close the throttle, pull the mixture to idle/cut-off, and switch the fuel selector valve to off.

The ground is approaching fast. I set the flaps and adjust my approach to avoid power lines I hadn’t noticed from cruising altitude. The large pylons are obvious from the ground, but from 3,000 feet, they blend into the dark green landscape and cast little shadow.

Once I have cleared the hazard, the landing field is ahead. Young green crops stretch out in orderly rows. No ditches, no obstacles, no people. A small village in the distance offers the possibility of help. Nearby windmills indicate a headwind—ideal for landing.

I set full flaps and trim for minimum approach speed. Then, I shut off the main electrical bus. I needed power to extend the flaps, but now that they are set, I cut all electricity to reduce ignition risks further. The last item on my mental checklist is the door handle. The Cessna has two doors. I unlock mine. The wind prevents it from opening fully, but it is cracked open just enough to ensure it won’t jam if the fuselage deforms on impact. Now, I am ready and completely focused on the landing

Suddenly, the engine roars back to life. The pitch changes, and my instructor’s voice breaks through the intercom: “I have control.” We begin climbing back to cruising altitude.

“D-EDUF, emergency drill completed,” he reports to air traffic control. I take us back to the airport.

We had planned these drills on the ground. I had practiced beforehand, yet I still missed some memory items in nearly every approach. Even in a training scenario, it is incredibly challenging to stay calm, keep the airplane under control, and systematically work through the emergency procedures.

To be continued…